Amanda Hawks, Dr. Whitney Douglas

Background

KEY TERM

Emotional Labor – First introduced by Arlie Russel Hoschild in the 1980’s, emotional labor refers to, labor that “requires one to induce or suppress feeling in order to sustain the outward countenance that produces the proper state of mind in others” (7). In other words, emotional labor is regulating your emotions in order to produce an emotional response in others. A great example of this is customer service voice which is used even when workers are depressed, distressed, or upset, in order to evoke a sense of comfort in customers.

Main Argument

My research argues that emotional labor is experienced differently by people of color, and for this project specifically, I’m examining the ways that people of color perform emotional labor in the workplace, specifically within writing centers.

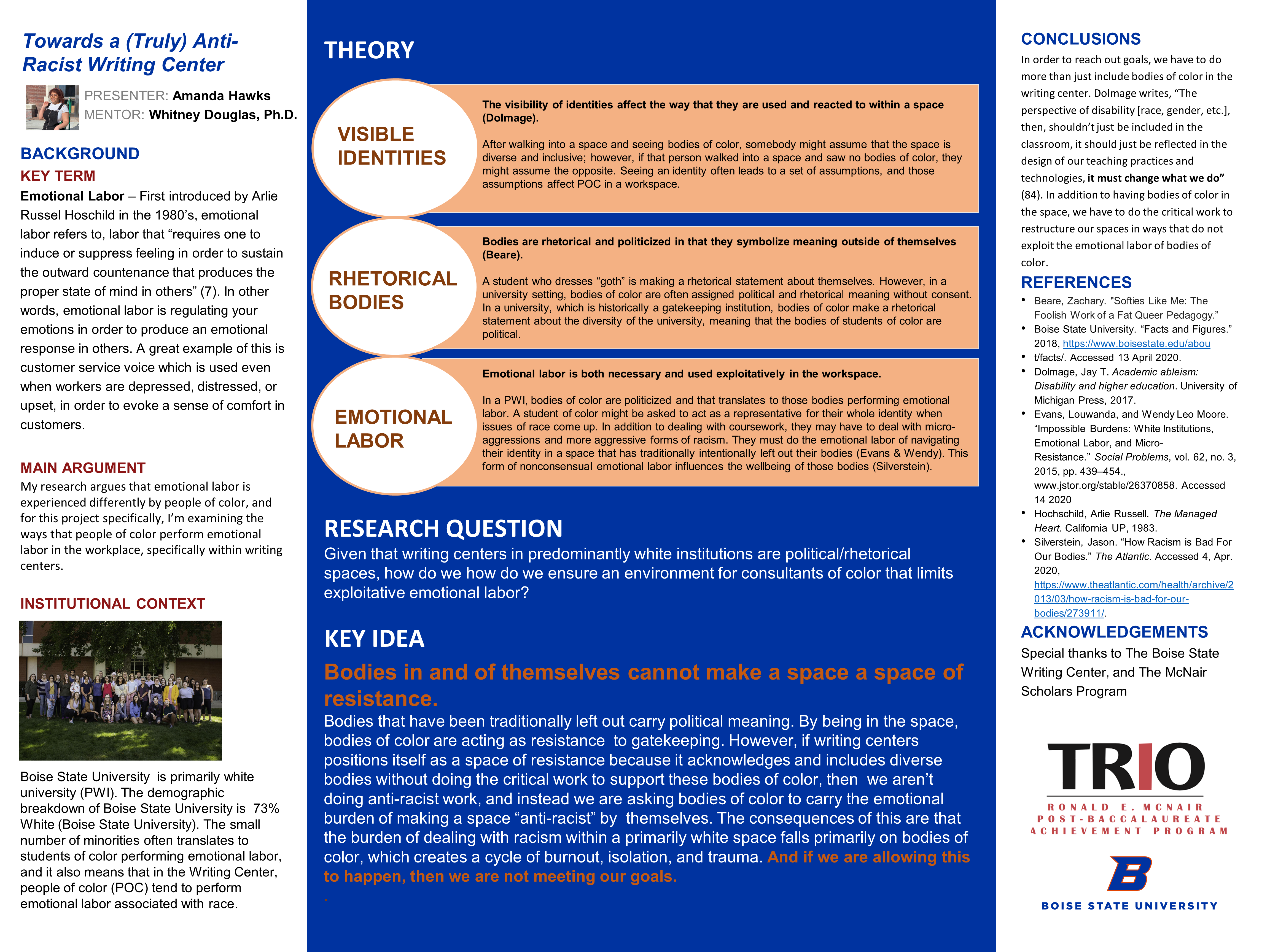

Institutional Context

Boise State University is primarily white university (PWI). The demographic breakdown of Boise State University is 73% White (Boise State University). The small number of minorities often translates to students of color performing emotional labor, and it also means that in the Writing Center, people of color (POC) tend to perform emotional labor associated with race.

Theory

VISIBLE IDENTITIES

The visibility of identities affect the way that they are used and reacted to within a space (Dolmage).

After walking into a space and seeing bodies of color, somebody might assume that the space is diverse and inclusive; however, if that person walked into a space and saw no bodies of color, they might assume the opposite. Seeing an identity often leads to a set of assumptions, and those assumptions affect POC in a workspace.

RHETORICAL BODIES

Bodies are rhetorical and politicized in that they symbolize meaning outside of themselves (Beare).

A student who dresses “goth” is making a rhetorical statement about themselves. However, in a university setting, bodies of color are often assigned political and rhetorical meaning without consent. In a university, which is historically a gatekeeping institution, bodies of color make a rhetorical statement about the diversity of the university, meaning that the bodies of students of color are political.

EMOTIONAL LABOR

Emotional labor is both necessary and used exploitatively in the workspace.

In a PWI, bodies of color are politicized and that translates to those bodies performing emotional labor. A student of color might be asked to act as a representative for their whole identity when issues of race come up. In addition to dealing with coursework, they may have to deal with micro-aggressions and more aggressive forms of racism. They must do the emotional labor of navigating their identity in a space that has traditionally intentionally left out their bodies (Evans & Wendy). This form of nonconsensual emotional labor influences the wellbeing of those bodies (Silverstein).

Research Question

Given that writing centers in predominantly white institutions are political/rhetorical spaces, how do we how do we ensure an environment for consultants of color that limits exploitative emotional labor?

Key Idea

Bodies in and of themselves cannot make a space a space of resistance.

Bodies that have been traditionally left out carry political meaning. By being in the space, bodies of color are acting as resistance to gatekeeping. However, if writing centers positions itself as a space of resistance because it acknowledges and includes diverse bodies without doing the critical work to support these bodies of color, then we aren’t doing anti-racist work, and instead we are asking bodies of color to carry the emotional burden of making a space “anti-racist” by themselves. The consequences of this are that the burden of dealing with racism within a primarily white space falls primarily on bodies of color, which creates a cycle of burnout, isolation, and trauma. And if we are allowing this to happen, then we are not meeting our goals.

Conclusions

In order to reach out goals, we have to do more than just include bodies of color in the writing center. Dolmage writes, “The perspective of disability [race, gender, etc.], then, shouldn’t just be included in the classroom, it should just be reflected in the design of our teaching practices and technologies, it must change what we do” (84). In addition to having bodies of color in the space, we have to do the critical work to restructure our spaces in ways that do not exploit the emotional labor of bodies of color.

References

- Beare, Zachary. “Softies Like Me: The Foolish Work of a Fat Queer Pedagogy.”

- Boise State University. “Facts and Figures.” 2018, https://www.boisestate.edu/abou

t/facts/. Accessed 13 April 2020. - Dolmage, Jay T. Academic ableism: Disability and higher education. University of Michigan Press, 2017.

Evans, Louwanda, and Wendy Leo Moore. “Impossible Burdens: White Institutions, Emotional Labor, and Micro-Resistance.” Social Problems, vol. 62, no. 3, 2015, pp. 439–454., www.jstor.org/stable/26370858. Accessed 14 2020 - Hochschild, Arlie Russell. The Managed Heart. California UP, 1983.

- Silverstein, Jason. “How Racism is Bad For Our Bodies.” The Atlantic. Accessed 4, Apr. 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/03/how-racism-is-bad-for-our-bodies/273911/.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to The Boise State Writing Center, and The McNair Scholars Program.

Additional Information

For questions or comments about this research, contact Amanda Hawks at amandahawks@u.boisestate.edu.