By Austin Young, Idaho State University Masters Student

For decades, eastern Idaho has been recognized as hosting some of the best birding in the state. Extensive mudflats and riparian woodlands, for example, provide excellent opportunities to observe migrant birds as they refuel and rest on their journey to breeding or overwintering sites. For songbirds in particular, this phenomenon has been well documented at Camas National Wildlife Refuge.

Between fall 2005 and spring 2007, IBO’s research director, Jay, and a team of ornithologists measured an impressive volume and diversity of migrant birds that were using Camas each spring and fall en route to their breeding and overwintering sites.

But in the years since then, the refuge has conspicuously changed, perhaps most notably the vegetation community.

These changes are mostly due to a combination of numerous drought years and increased agricultural use of upstream water. The refuge riparian woodland now comprises many dead and fallen cottonwoods, rows of primarily dead Russian Olive, and a remnant of live Box-elder and willow along Camas Creek along with several patches of Siberian pea.

In view of the vegetation change that has occurred at Camas over the last 17 years, the general inkling of biologists and birders is that the refuge is unable to support the migrant bird load it once did.

Now… is that true?

If so, is it the case for all species? If not, why not? Could the changes observed in migratory birds here also be potentially present in other areas of the American West that are experiencing similar change?

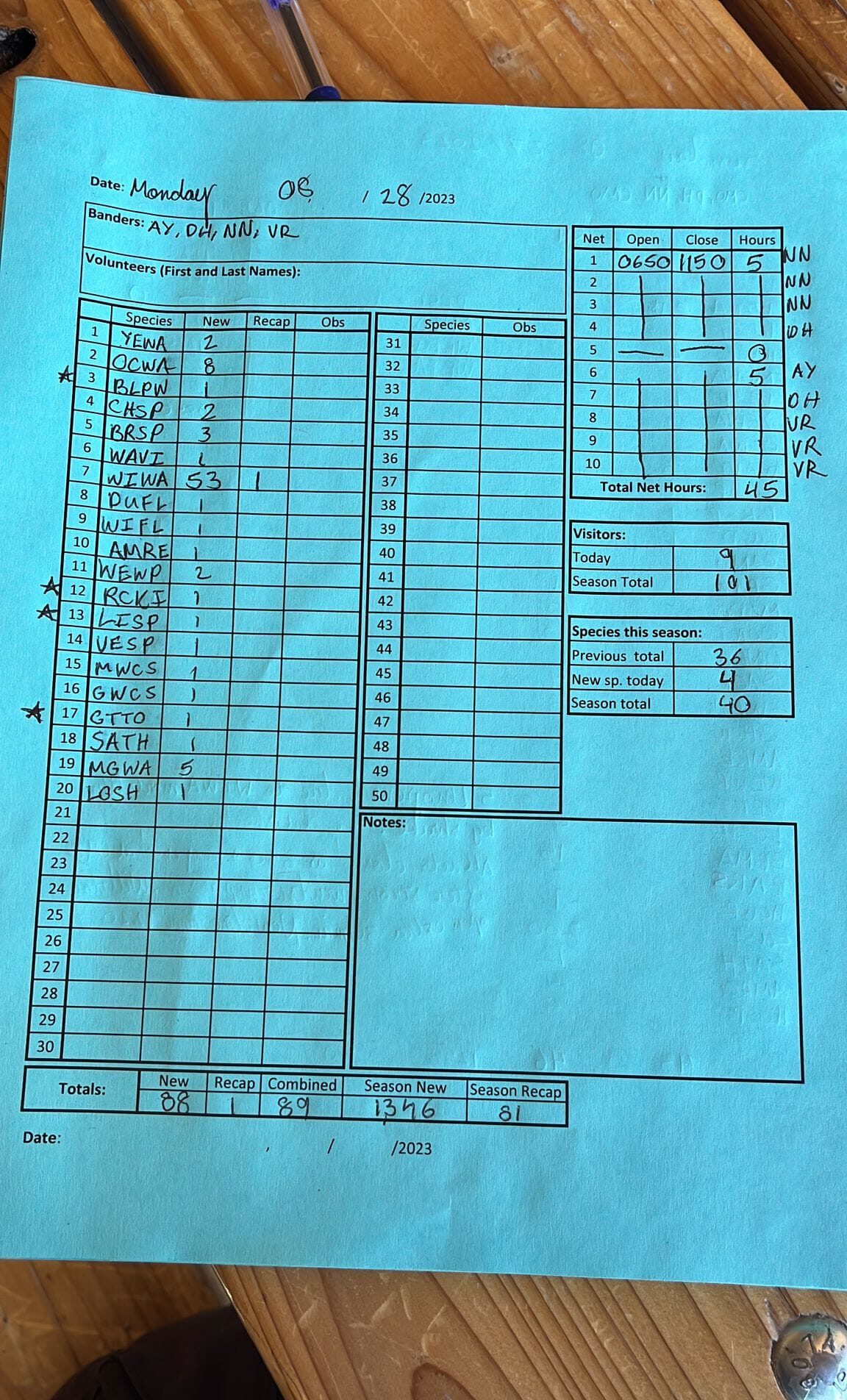

To help answer these questions and more, we launched a joint effort between IBO, Friends of Camas NWR, and myself, as an Idaho State University master’s degree-seeking student. The goal was to replicate the two-year historical songbird migration research in order to discover how the migrant bird community and individual bird behavior and morphology may have changed in light of the substantial vegetative changes. With a full-time banding crew in 2023, we executed a spring banding operation from April 16th through June 15th and an autumn banding session from July 21st through October 15th.

The spring banding proved to be quite cold and started out slow-paced in terms of captures, then suddenly picked up the last week of May and first week of June then tapered off again the last week of banding. In contrast, autumn was much more drawn out and peak migration lasted about a month from late August through late September. The fall migration was also much more pronounced, as expected, since many hatch-year birds were on the landscape making their first journey south.

In fact, there were more than a few days during which we captured 100+ birds!

A highlight was one particular net run on one of those high-volume bird days where, mixed in with the bottomless Wilson’s Warblers, were an American Redstart and Blackpoll Warbler!

The results after one spring and fall migration season of mist-netting were a mix of exciting, potentially concerning, and surprising findings. In the spring, we captured 1,412 individual birds comprising 65 species. This is approximately 25% less compared to historical numbers from the 2006 and 2007 spring migration banding seasons.

The autumn banding season documented a similar, but less stark, decrease in overall capture totals. The fall 2023 banding season produced a total of 3,930 individual birds comprising 73 species. This is an approximately 12% decrease from the 2005-2007 historical average of captured birds.

The story isn’t solely in the overall numbers.

We saw substantial shifts in abundance from the 2005-2007 totals relative to 2023 for many species. Species with substantially lower capture totals in 2023 (some with up to 67% lower abundances) included Wilson’s Warbler, Hermit Thrush, Ruby-crowned Kinglet, MacGillivray’s Warbler, Yellow Warbler, and Hammond’s Flycatcher. Wilson’s Warblers, for example, decreased from the historical annual total (spring + fall migration combined) of ~2,100 banded individuals to a total of 829 individuals in 2023.

On the other hand, species that were captured markedly more often in 2023 generally included open country species such as White-crowned Sparrow, House Sparrow, Sage Thrasher, Loggerhead Shrike, Northern Flicker, and even a handful of Common Nighthawks!

For example, the prior effort only captured four total House Sparrows from 2005-2007 but we had a whopping 372 House Sparrows in 2023 – most of which were concentrated in late July and early August, presumably a post-breeding dispersal phenomenon. We also captured 704 White-crowned Sparrows and 84 Sage Thrashers in 2023, far more than the historical totals of 249 White-crowned Sparrows and 2 Sage Thrashers combined across two years and four seasons!

Noteworthy species captured across both seasons included an Ovenbird, Blackpoll Warbler, Clay-colored Sparrow, and a surprising 10 White-throated Sparrows. Perhaps most exciting was the capture of a Black-throated Green Warbler…

…which was likely Idaho’s 3rd confirmed record!

It’s difficult to interpret such extensive, population-level data without multiple years of remeasuring the same variables. Thus, next year we will continue banding at Camas for one more spring and fall season so that we can have 2 full spring and fall migration seasons during each period (fall 2005 to spring 2007 and spring 2023 through fall 2024) to compare. This winter will be chock-full of analyzing this huge amount of data!

For me, this work will culminate into a thesis defense in the spring of 2024.

While measuring bird migration has been extremely rewarding and eventful, I would be neglectful to not reminisce on the extensive education and outreach that the banding station accomplished this past year.

Eastern Idaho receives very little publicly available ornithological attention, so regionally, songbird banding was a big deal !

Local writers published a handful of articles about the station and the work we are doing there. Hundreds of people were able to visit and learn all about birds, banding, migration, and stopover ecology.

This project is a huge effort that could not have been possible without the support we have received from many partners, including Friends of Camas NWR. They have been working towards replicating the historical research for over a decade and have succeeded in raising the funds needed.

We literally would not be here without their diligent efforts.

Other funding sources include Portneuf Valley Audubon Society, Snake River Audubon Society, and Idaho State University. Furthermore, I am very thankful for the housing and logistical support provided by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game and Camas NWR refuge staff. This past year was a success, and we are excited to see what next year holds. We hope to see you out there in the spring beginning April 16th!

This article is part of our 2023 end of the year newsletter! View the full newsletter here, or click “older posts” below to read the next article.

Make sure you don’t miss out on IBO news! Sign up to get our email updates.